Table of Contents

- General Overview

- 1.1 Mechanism of Action

- 1.2 The Ego Death

- Safety Profile

- Use in Ancient Cultures

- Clinical Potential

- 4.1 Macrodosing

- 4.2 Microdosing

- References

An image resembling the visuals seen during very high doses of psilocybin.

1. General Overview

Psychedelics are a class of hallucinogenic drugs (“hallucinogens”) that produce mind-altering and reality-distorting effects technically called hallucinations. However, the sorts of hallucinations experienced by schizophrenics are very different from the visual distortions experienced by psychedelics. Also, schizophrenic hallucinations are never triggered by psychedelics, but only by stimulant drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine, which increase levels of dopamine (See: The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia). In turn, antipsychotic medications used to treat disorders such as schizophrenia decrease the levels of dopamine, making people sluggish and demotivated.

A friend and science author, Anticode, explains the connection:

“One of [the schizophrenics I befriended], more introspective than the others, remarked that the delusions and confusion is typically accompanied by a “eureka moment”. He said that this made it very difficult to ignore the nonsense because they felt, beyond a doubt, like good, right ideas. They felt like truth in the way that only truth can (its chemical manifestation, at least). The same sort of dopamine-ping (which is a reinforcer more than it is a motivator—important distinction) is present when manic people drift into psychosis. One too many dopamine pings, one too many errant thoughts integrated as valid-beyond-a-doubt. Same with amphetamine psychosis. Dopamine goes apeshit. Everything feels meaningful so people become a slavering wreck as their brain continuously reinforces neural pathways that serve no purpose or have no value.”

And from Nature, a weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology, No Link Found between Psychedelics and Psychosis:

“Data from population surveys in the United States challenge public fears that psychedelic drugs such as LSD can lead to psychosis and other mental-health conditions and to increased risk of suicide. The findings are likely to raise eyebrows. Fears that psychedelics can lead to psychosis date to the 1960s, with widespread reports of “acid casualties” in the mainstream news. But Krebs says that because psychotic disorders are relatively prevalent, affecting about one in 50 people, correlations can often be mistaken for causations. “Psychedelics are psychologically intense, and many people will blame anything that happens for the rest of their lives on a psychedelic experience.”

Psychedelics work differently from other drugs in that they don't induce any particular feeling. For instance, cocaine increases dopamine, making the user feel awake, motivated, euphoric, et cetera. Valium increases GABA, producing relaxing effects and slowing neuronal firing. On the other hand, psychedelics have a more general impact on the functioning and connectivity of the brain.

Joe Rogan partially explains his experience with this idea:

1.1 Mechanism of Action

Psychedelics change the functioning of the brain by decreasing activity in the Default Mode Network (DMN). Meditation also reduces default mode network activity (Garrison et al., 2016). The DMN is responsible for internal mental-state processes, such as self-referential processing, interoception, autobiographical memory retrieval, or imagining the future. The functional connections that make up the DMN increase from birth to adulthood, and it mainly emerges around the age of five as the child develops a stable sense of narrative self or “ego”.

DMN activity is also associated with self-consciousness, a facet of trait neuroticism. (See: Psychedelics and the Default Mode Network). In fact, the amount of I's used in an author's writing is a predictor of suicidality.

Anticode explains this connection simply:

“I imagine that the usage of I's corresponds to general self awareness, relating to introspection, relating to rumination; which is of course the whirlpool that fuels the engine of self-destruction.”

And from the Psychonaut Wiki:

“The mechanism behind [psilocybin's antidepressant effects] is not known as of yet, but researchers have suggested that psilocin's deactivation [a brain part that is strongly associated with depression and] with trait rumination”

This is thought to explain the markedly increased emotional empathy on psilocybin (Pokorny et. al, 2017), as well as the “mystical experience” (More on this on section 4.2 Macrodosing) that occurs with both psychedelics and intensive meditation:

“Ego dissolution experiences often occur in the context of mystical states in which the ordinary sense of self is replaced by a sense of union with an ultimate reality underlying all of manifest existence—the famous ‘cosmic consciousness’ experience. [...] The propensity of psychedelics to occasion such experiences goes some way to explaining their history of religious use. Indeed, intellectuals such as Watts and Aldous Huxley were initially drawn to psychedelics due to a prior interest in mysticism. With respect to ego dissolution, it is worth noting that apprehending the non-existence of the individual self is a central goal of Buddhist meditation (Albahari 2014). There is evidence that mystical states are important for the therapeutic effects of psychedelics (Garcia-Romeu et al. 2016) so explaining the ego dissolution experience is a crucial step in theorizing the mechanisms of psychedelic treatment.”

As we mature, we learn to respond to life’s stimuli in a patterned way, developing habitual pathways of communication between brain regions. Over time, communication solidifies and becomes confined to specific pathways, meaning that our brain becomes more ‘constrained’ as we develop. It is these constrained paths of communication between brain regions that quite literally come to constitute our ‘default mode’ of operating in the world, colouring the way we perceive reality.

Evolutionarily speaking, it has been hypothesised that the DMN plays a major role in our survival, helping us form a continuous sense of self, differentiating ourselves from the world around us.

This is how psychedelics change the connectivity of the brain: by increasing communication between brain regions that are normally compartmentalised (Carhart-Harris et. al, 2014). This is thought to explain anecdotal claims that one can “communicate” with their subconscious/unconscious on high-enough doses of psychedelics, especially magic mushrooms and ayahuasca (See the article: Psilocybin Mushrooms: The Window into My Subconscious).

The diagram above demonstrates the neural connections associated with sobriety in comparison to being under the influence of psilocybin as demonstrated through the use of MRI scans. The width of the links is proportional to their weight and the size of the nodes is proportional to their strength. Note that the proportion of heavy links between communities is much higher (and very different) in the psilocybin group, suggesting greater integration (Petri et al., 2014)1.2 The Ego Death

Buddhism and many other contemplative traditions have long argued that on close investigation, there doesn’t appear to be any deeper “you” in there running the show. “You” are just a flimsy identification process, built on the fly by your interpreter module. To better understand this idea, consider the following quotes from Jonathan Haidt (2006, pp.8-9).

First, background information: The brain is made up of several different regions, each of which evolved at different points in the evolutionary timeline and serve different purposes for survival. Additionally, the brain is divided into two hemispheres, which are connected by a large bundle of nerves. Split-brain patients have this connection cut so that the two hemispheres no longer directly communicate. The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and vice-versa.

“When Gazzanig a flashed different pictures to the two hemispheres, [...] On one occasion he flashed a picture of a chicken claw on the right, and a picture of a house and a car covered in snow on the left. The patient was then shown an array of pictures and asked to point to the one that "goes with" what he had seen. The patient's right hand pointed to a picture of a chicken (which went with the chicken claw the left hemisphere had seen), but the left hand pointed to a picture of a shovel (which went with the snow scene presented to the right hemisphere). When the patient was asked to explain his two responses, he did not say, "I have no idea why my left hand is pointing to a shovel; it must be something you showed my right brain." Instead, the left hemisphere instantly made up a plausible story. The patient said, without any hesitation, "Oh, that's easy. The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed."

[...]Gazzaniga refers to the language centers on the left side of the brain as the interpreter module, whose job is to give a running commentary on whatever the self is doing, even though the interpreter module has no access to the real causes or motives of the self's behavior. For example , if the word "walk" is flashed to the right hemisphere, the patient might stand up and walk away. When asked why he is getting up, he might say, "I'm going to get a Coke." The interpreter module is good at making up explanations, but not at knowing that it has done so.

[...]These dramatic splits of the mind are caused by rare splits of the brain. Normal people are not split-brained. Yet the split-brain studies were important in psychology because they showed in such an eerie way that the mind is a confederation of modules capable of working independently and even, sometimes, at cross-purposes. Split-brain studies are important for this book because they show in such a dramatic way that one of these modules is good at inventing convincing explanations for your behavior, even when it has no knowledge of the causes of your behavior. Gazzaniga's "interpreter module " is, essentially, the rider.”

The classic result of successful Buddhist practices is to permanently recognise the impermanence (anicca) and the selflessness (anatta) of all experience. For most people, this shift is the most profoundly positive experience of their lives.

As Alan Watts (1989, pp.15) put it:

“I seem to be a brief light that flashes but once in all the aeons of time—a rare, complicated, and all-too-delicate organism on the fringe of biological evolution, where the wave of life bursts into individual, sparkling, and multicolored drops that gleam for a moment only to vanish forever. Under such conditioning it seems impossible and even absurd to realize that myself does not reside in the drop alone, but in the whole surge of energy which ranges from the galaxies to the nuclear fields in my body. At this level of existence “I” am immeasurably old; my forms are infinite and their comings and goings are simply the pulses or vibrations of a single and eternal flow of energy.”

Get a better idea by watching this animation by the creators of South Park over one of Alan Wats' lectures:

Psychedelics can be a 'shortcut' to achieving these insights. When achieved, users report feeling like pure awareness, having a feeling of oneness with all, and an experience of unity with ultimate reality. In the scientific literature, this is called the mystical-type experience, which is responsible for most of the therapeutic potential of psychedelics (Sessa et al., 2020). MEs have been shown in previous research (e.g., Griffiths, Richards, McCann, & Jesse, 2006) to be related to long-term positive personal change. More on this in 4.2 Macrodosing.

Although psychedelics are among the safest drugs (See: 2. Safety Profile ), an ego-death can be psychologically dangerous; the sense of selflessness or 'ego death' accompanied by psychedelics is the main cause of the long-term negative consequences. First, consider that in meditative practices, the user slowly trains themselves to observe their thoughts and decrease activity in the DMN until the state of ego death occurs organically. Even then, Shinzen Young, a Buddhist teacher, has pointed at the difficulty of integrating the experience of no-self. He calls this “the Dark Night”, or:

“[...] "falling into the Pit of the Void." It entails an authentic and irreversible insight into Emptiness and No Self. What makes it problematic is that the person interprets it as a bad trip. Instead of being empowering and fulfilling, the way Buddhist literature claims it will be, it turns into the opposite. In a sense, it's Enlightenment's Evil Twin.”

However, Young says that for the great majority of people, the nature, intensity, and duration of these kinds of challenges is quite manageable.

(Shinzen Young, 2011) Additionally, within meditative traditions, classic texts talk about the “dukkha ñanas” – challenging stages that are actually a sign of progress. These are a natural response to the layer of mind being stripped away and exposed.

In scientific literature, this Dark Night experience is often called depersonalisation.

From the paper titled Meditation and Depersonalization (1990), which reviewed the literature on meditation and depersonalization and interviews conducted with meditators, from the Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, the description of the state of depersonalization sounds exactly like the goal of mindfulness meditation:

“Typically, depersonalization is a state in which an individual experiences a "split" in consciousness between a "participating self" and an "observing self." The participating self is composed of body, thoughts, feelings, memories, and emotions. The observing self is experienced as a searate, uninvolved "witness" of the participating self, with the perception that all of the normal aspects of personality are somehow unreal and do not belong to the observing self.”[...]

“It seems as if they are not doing if because they can observe an independent flow of these phenomena in their minds. -----Kennedy reported two cases in which patients experienced depersonalization and derealization as a result of meditation practices and suffered sufficient anxiety as a result of their depersonalization to seek psychiatric treatment. In the first of these cases, the patient (a 37-year-old businessman) developed the feeling of being outside his body and looking down on himself after experimenting with a series of meditative exercises described in a book entitled Awareness (Stevens 1971). The patient continued with these experiments over several days until depersonalization and derealization experiences began to occur spontaneously and uncontrollably. The patient sought admission at a local hospital and was treated with tranquilizers and released. However, he sought readmission a few days later in a state of panic because the tranquilizers he had been given (type unstated) seemed to exacerbate his· feelings of unreality. During this second hospitalization ECT was proposed, but the patient refused and was discharged. On the advice of a friend he sought help from a Yoga instructor. The patient stayed with the Yoga instructor for several days, learning about his experiences from the perspective of Yoga psychology. He was then able to return to work, even though the episodes continued to occur, because he felt he had gained enough insight into the occurrences so that he was no longer bothered by them.”

The crucial difference whether one seeks treatment for depersonalization or whether one feels enlightened from meditation or psychedelics, it seems, is what the paper describes here:

“The intriguing aspect of [depersonalization] is that apparently by using virtually the same mental maneuvers [as meditation] a syndrome may be produced that, depending on the attitude the person adopts toward himself and then toward the resulting phenomenon, may be experienced either as something to be sought and valued or as something to be feared and called a disease. Perhaps what we need to do with patients who exhibit primarily a depersonalization syndrome is to teach them first to accept themselves uncritically and second to accept their depersonalization. [p. 1327]

In these cases, depersonalization occurred first and was followed by panic/anxiety. It is significant that in both cases panic/anxiety was relieved and occupational functioning restored by the reconstruction of the subjective meaning of the depersonalization in the mind of the patient. This was true even though episodes of depersonalization continued. In medical anthropology this therapeutic process involving the transformation of ideational and emotional factors is known as symbolic healing.”

As such, the paper came to the following six conclusions:

- Meditation can cause depersonalization and derealization.

- The meanings in the mind of the meditator regarding the experience of depersonalization will determine to a great extent whether anxiety is present as part of the experience.

- There need not be any significant anxiety or impairment in social or occupational functioning as a result of depersonalization.

- A depersonalized state can become an apparently permanent mode of functioning.

- Patients with Depersonalization Disorder may be treated through a process of symbolic healing that is, changing the meanings associated with depersonalization in the mind of the patient, thereby reducing anxiety and functional impairment.

- Panic/ anxiety may be caused by depersonalization if catastrophic interpretations of depersonalization are present.

Likewise, when it comes to psychedelics, depersonalization and the associated anxiety come from acceptance. Bad trips with psychedelics are usually a result of not surrendering to the experiences and the new state of consciousness.

From Aday et al's (2021) Predicting Reactions to Psychedelic Drugs: A Systematic Review of States and Traits Related to Acute Drug Effects:

“Individuals high in the traits of absorption, openness, and acceptance as well as a state of surrender were far more likely to have positive and mystical-type experiences, whereas those low in openness and surrender or in preoccupied, apprehensive, or confused psychological states were more likely to experience acute adverse reactions.

[...] Thus, absorption, openness, and acceptance may represent a set of related personality traits that prime individuals to fully immersive themselves in, and be more accepting of, a nonordinary state”

The paper defined surrender as the “willful release of one’s goals, constructs, habits, and preferences”.

As shown in the graph below, acceptance and surrender were the two best predictors of having a mystical-type experience rather than having adverse effects:

The researchers found that both surrender and acceptance were also positively related to spiritual change and long-term positive change, as well as negatively associated with acute experiences of dread and long-term negative change (such as depersonalization).

In this particular paper, a more thorough definition of surrender was given:

“Surrender: religious conversion characterized by “passivity, not activity; relaxation, not intentness,” a readiness to “give up the feeling of responsibility, let go your hold, resign the care of your destiny to higher powers, be genuinely indifferent as to what becomes of it all” (p. 67). This is supported in the extensive analysis of qualitative records of transformative ME conducted by Miller and C’De Baca (2001).”

State of surrender (SoS). The state of surrender is defined as a readiness to accept whatever was, whether good or bad, without resisting or fighting or struggling. The final 10-item scale included “I had stopped resisting and was ready to give up control” and “I’d felt a release from the need to think so hard.” Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .91. See Table T3 in the online supplemental materials.”

Additionally, clear intentions about the goal of the psychedelic experience were also strongly predictive of mystical-type experiences.

2. Safety Profile

Psilocybin is non-addictive, does not cause brain damage, and has an extremely low toxicity relative to dose. Similar to other psychedelic drugs, there are relatively few physical side effects associated with acute psilocin exposure. Various studies have shown that in reasonable doses in a careful context, it presents extremely little to no negative cognitive, psychiatric or toxic physical consequences.

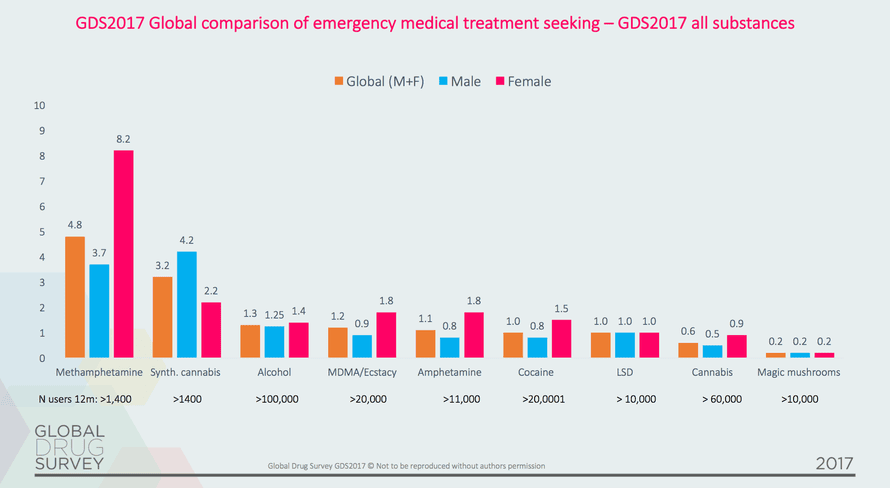

From the research company Global Drug Survey, which runs the biggest drug survey in the world:

And a slide from the 2017 GDS summary:

From a different paper, Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis:

"Members of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, including two invited specialists, [scored] 20 drugs on 16 criteria. [T]he criteria were weighted to indicate their relative importance."

See page 8 of the paper's PDF for more detail on each criterion. Click here for a direct download.

This multicriteria decision analysis paper also compared their results to the nine-criteria analysis undertaken by UK experts and the output of a Dutch population, where drug use is far less biased by legality and availability:

"The highest and lowest scores for the Dutch individual ratings ( were 2·63 for crack cocaine and 0·40 for mushrooms, which is a ratio of 6·6:1"

"The correlations between the Dutch addiction medicine expert group2 and ISCD results are higher: 0·80 for individual total scores and 0·84 for population total scores"

Note that in this type of research, correlations of 0.8 are already considered high due to the amount of noise (confounding variables) in the measurements.

Lastly, it should be clear by now that of all psychedelic substances, psilocybin is the safest. From a review of several peer-reviewed studies, "The Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin":

"Of all psychedelic drugs, psilocybin [the active chemical in magic mushrooms] is reported to have the most favorable safety profile [13]. Despite the lack of studies investigating the comparative efficacies of psilocybin and psychedelic drugs for the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders, the vast evidence-based data that exist for psilocybin alone suggest that psilocybin may be the most efficacious psychedelic drug for treating such disorders.

In summary, the risk of taking magic mushrooms is almost entirely attributed to problems in set, setting and dosage (See the study Psychedelics and the essential importance of context). People who take extremely high doses in a bad state of mind and environment can end up developing depersonalization and anxiety, which mainly stems from PTSD as discussed in section 1.2 The Ego Death.

3. Use in Ancient Cultures

There is strong evidence to suggest that psychoactive mushrooms have been used by humans in religious ceremonies for thousands of years. 6,000-year-old pictographs discovered near the Spanish town of Villar del Humo illustrate several mushrooms that have been tentatively identified as Psilocybe hispanica, a hallucinogenic species native to the area (Akers, Ruiz, Piper and Ruck, 2011).

In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the mushrooms were called teonanácatl, or "God's flesh". Following the arrival of Spanish explorers to the New World in the sixteenth century, chroniclers reported the use of mushrooms by the natives for ceremonial and religious purposes. According to the Dominican friar Diego Durán in The History of the Indies of New Spain (published c. 1581), mushrooms were eaten in festivities conducted on the occasion of the accession to the throne of Aztec emperor Moctezuma II in 1502. The Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún wrote of witnessing mushroom usage in his Florentine Codex (published 1545–1590),(Marley, 2011) and described how some merchants would celebrate upon returning from a successful business trip by consuming mushrooms to evoke revelatory visions (Hofmann, 2009).

What's really interesting to me is that the active chemical in magic mushrooms, which has been used by natives throughout the world, is almost identical (and produces extremely similar experiences to) the active chemical in ayahuasca, DMT, which is also used in rituals by natives from South America, especially in the Amazon.

Ayahusca has DMT, which, as you can see, only slightly differs from psilocin (the active chemical in magic mushrooms) by lacking an OH- bond:

Evidence of ayahuasca use dates back 1,000 years, as demonstrated by a bundle containing the residue of ayahuasca ingredients and various other preserved shamanic substances in a cave in southwestern Bolivia, discovered in 2010 (Miller, Albarracin-Jordan, Moore and Capriles, 2019)

The uses of ayahuasca in traditional societies in South America vary greatly. Some cultures do use it for shamanic purposes, but in other cases, it is consumed socially among friends, in order to learn more about the natural environment, and even in order to visit friends and family who are far away (Hay, 2020)

Shamans, Curanderos and experienced users of ayahuasca advise against consuming ayahuasca when not in the presence of one or several well-trained shamans (Campos, 2011)

The shamans lead the ceremonial consumption of the ayahuasca beverage (Morris, 2014), in a rite that typically takes place over the entire night. During the ceremony, the effect of the drink lasts for hours. Prior to the ceremony, participants are instructed to abstain from spicy foods, red meat and sex (See: Ayahuasca Ceremony Preparation). The ceremony is usually accompanied with purging which include vomiting and diarrhea, which is believed to release built-up emotions and negative energy (See: The New Power Trip: Inside the World of Ayahuasca).

4. Clinical potential

Most of the studies finding long-lasting benefits across many areas of people's lives come from psilocybin-induced mystical experiences. These mystical experiences, as discussed in 1. General Overview, can be occasioned by meditation and higher doses of psychedelics. However, there are also studies finding that taking psychedelics (primarily psilocybin) at sub-perceptual doses can have many temporary benefits at little cost, and potentially longterm benefits. I cover these respectively in 4.1 Macrodosing and 4.2 Microdosing.

4.1 Macrodosing

Clinical potential of psilocybin as a treatment for mental health conditions: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6007659/

In a small study of adults with major depression, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers report that two doses of the psychedelic substance psilocybin, given with supportive psychotherapy, produced rapid and large reductions in depressive symptoms: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/psychedelic-treatment-with-psilocybin-relieves-major-depression-study-shows

Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5367557/

Dosage given in Griffiths' studies:

Participants report it being one of the most meaningful experiences of their life:

Participants who had the mystical experience increased by one standard deviation in openness to experience:

4.2 Microdosing

Can Microdosing Psychedelics Improve Your Mental Health? https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2020/can-microdosing-psychedelics-improve-your-mental-health/

Psychedelic microdosing benefits and challenges: an empirical codebook: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-019-0308-4

The therapeutic potential of microdosing psychedelics in depression: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2045125320950567

5. References

Aday, J., Davis, A., Mitzkovitz, C., Bloesch, E. and Davoli, C., 2021. Predicting Reactions to Psychedelic Drugs: A Systematic Review of States and Traits Related to Acute Drug Effects. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), pp.424-435.

Albahari, M., 2014. Insight Knowledge of No Self in Buddhism: An Epistemic Analysis. Philosophers Imprint, 14(21).

Akers, B., Ruiz, J., Piper, A. and Ruck, C., 2011. A Prehistoric Mural in Spain Depicting Neurotropic Psilocybe Mushrooms?1. Economic Botany, 65(2), pp.121-128.

Carhart-Harris, R., Leech, R., Hellyer, P., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., Chialvo, D. and Nutt, D., 2014. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8.

Carhart-Harris, R., Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Erritzoe, D., Watts, R., Branchi, I. and Kaelen, M., 2018. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(7), pp.725-731.

Castillo, R., 1990. Depersonalizatipn and Meditation. Psychiatry, 53(2), pp.158-168.

Cormier, Z., 2015. No Link Found between Psychedelics and Psychosis. Nature, [online] Available at: <https://rdcu.be/cBk5H> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Garcia-Romeu, A., Kersgaard, B. and Addy, P., 2016. Clinical applications of hallucinogens: A review. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(4), pp.229-268.

Garrison, K., Zeffiro, T., Scheinost, D., Constable, R. and Brewer, J., 2015. Meditation leads to reduced default mode network activity beyond an active task. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15(3), pp.712-720.

Goodman, E., 2021. Psilocybin Mushrooms: The Window into My Subconscious - Elissa Goodman. [online] Elissa Goodman. Available at: <https://elissagoodman.com/lifestyle/psilocybin/> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Griffiths, R., Richards, W., McCann, U. and Jesse, R., 2006. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), pp.268-283.

Haidt, J., 2006. The happiness hypothesis. New York: Basic Books.

Haidt, J., 2006. The Happiness Hypothesis. Basic Books, pp.8-9.

Hofmann, A., 2009. LSD, my problem child. Santa Cruz, Calif.: MAPS, Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

James, E., Robertshaw, T., Hoskins, M. and Sessa, B., 2020. Psilocybin occasioned mystical‐type experiences. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 35(5).

Marley, G., 2011. Chanterelle dreams, amanita nightmares - the love, lore and mystique of mus. Chelsea Green Publishing Company, pp.163-184.

Miller, M., Albarracin-Jordan, J., Moore, C. and Capriles, J., 2019. Chemical evidence for the use of multiple psychotropic plants in a 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from South America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(23), pp.11207-11212.

Nutt, D., King, L. and Phillips, L., 2010. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet, 376(9752), pp.1558-1565.

Petri, G., Expert, P., Turkheimer, F., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D., Hellyer, P. and Vaccarino, F., 2014. Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 11(101), p.20140873.

Pokorny, T., Preller, K., Kometer, M., Dziobek, I. and Vollenweider, F., 2017. Effect of Psilocybin on Empathy and Moral Decision-Making. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(9), pp.747-757.

PsychonautWiki contributors, 2021. Psilocybin mushrooms. [online] Psychonautwiki.org. Available at: <https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Psilocybin_mushrooms#Antidepressant_effects> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Rege, D., 2021. The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia - Advances in Neurobiology. [online] Psych Scene Hub. Available at: <https://psychscenehub.com/psychinsights/the-dopamine-hypothesis-of-schizophrenia/> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Vaillant G., 2002. Quantum Change: When Epiphanies and Sudden Insights Transform Ordinary Lives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), pp.1620-1621.

Virdi, J., 2020. Psychedelics and the Default Mode Network. [online] Psychedelics Today. Available at: <https://psychedelicstoday.com/2020/02/04/psychedelics-and-the-default-mode-network/> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Warren, J., 2014. Enlightenment’s Evil Twin. Psychology Tomorrow, [online] Available at: <https://psychologytomorrowmagazine.com/popuartic-enlightenments-evil-twin/> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

Watts, A., 1989. The book on the taboo of knowing who you are. New York: Vintage Books.

Winstock, A., Barratt, M., Ferris, J. and Maier, L., 2017. GDS2017 - key findings report. [ebook] Available at: <https://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/wp-content/themes/globaldrugsurvey/results/GDS2017_key-findings-report_final.pdf> [Accessed 14 November 2021].